I like coffee. I really like coffee, when done right.

At its heart, coffee is one of the simplest beverages there is. How hard can it be to mix some beans with water? Pretty hard, it seems – finding a decent cup of coffee in town is hit or miss. We all have our personal preferences in coffee; with sugar or without, take or leave the milk, big or small cups, strong or weak.

I think coffee should be about more than just the caffeine. To me, the ideal coffee should speak for itself. Aromatic and strong, smooth, not overly bitter nor acidic and with a long-lingering, pleasant aftertaste – A coffee so good that it stands on it own and doesn’t need any additives.

And then there’s Britain, where tubs-full of Douwe Egberts instant granules are the norm. I believe this contributes greatly to the popularity of tea.

You can do a better job at mixing beans with water than that.

If the tips below don’t improve your brew at home, then either you’re not using them, or you’re worse coffee geek than I am and I respectfully salute you.

A good cup of coffee is down to two things: Ingredients and preparation.

1. Ingredients

1.1 Water

Water is the canvas that carries the flavour of coffee. Any water is fine as long as it has no off flavours. If you must, use filtered or bottled water; but most likely, as long as the water doesn’t taste chlorinated, it will be fine. Water will lose most of its chlorinated taste if left to stand for a while, if boiled or when passed through a water filter. If not filtered, it might still have a slight earthy taste on its own, as indeed do some coffee beans – you likely won’t be able to tell much of a difference in the final product.

1.2 Coffee beans

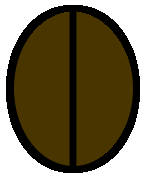

Coffee beans, the seeds of the berry of the coffee plant, are of course the most important ingredient of coffee. They are what provides coffee with most of its flavour, aroma, and of course caffeine. There are several varieties; the most notable being Robusta and Arabica. There is a visual distinction: Arabica beans are more elongated, and the slit in the bean tends to be more wave-shaped; Robusta beans are rounder and the slit is mostly straight (see below). Note that in reality the difference in slit is slightly less pronounced.

|

|

|

|

|

Robusta |

Arabica |

|

1.2.1. Variety

For best flavour, generally you’d want to avoid Robusta. Robusta has more caffeine and grows quicker, but also has a reputation for tasting like burned rubber. Arabica takes more care to grow, but is more aromatic. From a cost perspective, Robusta is cheaper, but when coffee is pure Arabica, only, this is considered a selling point; from a food labelling point of view, this means that pure Arabica coffee is typically labelled as such, while often no mention is made of the bean varieties if Robusta beans are present in the blend.

Choose coffee known to be pure Arabica.

If it’s caffeine you want, you can always drink more coffee. It’s more pleasant to drink two cups of nice coffee than to drink one cup of bad coffee.

1.2.1.1. Origin

Yes, coffee has terroir – beans from different places around the planet will have different flavour profiles. African varieties have a tendency to be fruity and bright; Coffees from the Americas tend to be full-bodied and sweet; Asian coffees tend to be earthy and spicy.

1.2.2 Beans vs. ground coffee

Once roasted and ground, coffee will quickly lose its aroma and go stale. Pre-ground coffee will taste best on the day of opening and will already take on stale notes the day after. Go for beans, grind them just before brewing. Maybe you think, “Ugh, aroma, who could possibly want that?” You’re in luck; leaving pre-ground coffee sitting in a doser until a client finally comes along is deemed acceptable by certain red-clad coffee houses, so if aroma isn’t your thing, they’ve got you covered.

I’d say there is one notable exception to using pre-ground coffee. Pre-ground coffee will taste fine every time if it’s the sort that’s individually sealed, be it pods or capsules. It will result in quite a bit of packaging waste, though… and frankly, flavour-wise, we can still do better than that. So I’d say go for beans. Not only will this result in less wasted packaging, but it will also protect you from any sort of vendor lock-in, should that matter to you.

There is another reason to go for coffee beans instead of pre-ground coffee, depending on the sort of country you get your coffee from: Coffee beans are far more difficult to adulterate with non-coffee ingredients than pre-ground coffee.

1.2.3 Storage

Air-tight storage is recommended. Pickling jars are great. Cooled storage or not? It depends. Moisture is the enemy of aroma and as such condensation is bad, but if you’ve bought roasted beans, they’ll keep about a week. There’s no need for refrigeration if your typical batch lasts about a week, but if it takes you much longer to consume a batch of coffee than that, reduce your batch size or freeze part of the batch. Repeated freeze/defrost cycles may adversely impact the quality of the beans, but coffee beans that have been frozen for a month taste considerably better than coffee beans that have merely been stored air tight. Take note: This is especially useful for keeping coffee beans fresh at a friend’s house, if they mostly drink tea or instant coffee. Friends don’t let friends drink bad coffee.

2. Preparation

Regardless of your preferred style of coffee, there are a few things you can do to get the most out of your coffee.

2.1. Cleanliness

The cleanliness of coffee-making equipment is heavily under-appreciated. It’s easy for mould and bacteria to grow on your coffee equipment and taint it with a perpetually stale coffee taste – especially when the coffee maker is not used every day. The high temperature at which coffee is brewed is typically fairly hostile to the moulds that like coffee, so regular use of your coffee maker will prevent these from growing and make coffee taste better. If your coffee maker is tainted with stale taste, replace it or give it a thorough clean – first with bicarbonate of soda, then with citric acid, then rinse it thoroughly.

2.2. Extraction

Extraction is the point at which water is in contact with your coffee grounds. It is the extraction phase that decides which aromas of your roasted beans end up in your coffee. If you have an espresso maker, you may have heard “90 Celcius, 8 grams, 30 ml, 9 bar, 20-25 seconds” as a guideline. This works, but it’s not the entire story. If your coffee maker happens to brew at a pressure of 16 bar and you grind your coffee fine enough for it to take 20-25 seconds to extract, your coffee will be over-extracted and taste bitter as the amount of quinic acid in you brew increases. For 16-bar machines, the sweet spot will be around 15-16 seconds (with slight variations per machine). So in this case,

pressure in bar * extraction time in seconds =~ 240

Of course with a personal sample size of exactly 3 espresso makers it’s probably pretentious to think this would apply to every coffee machine and every method of brewing coffee, though it does happen to match up with the roughly 4 minutes of brewing time recommended for French press coffee. Whatever you do, don’t blindly follow the numbers. Use your taste buds as the ultimate tool discover what pressure and brewing time give you the best result.

2.2.1. Amount of coffee to use

The amount of coffee to use depends largely on taste. A “standard” cup of coffee uses a ratio of roughly 60 grams of ground coffee to 1 liter of water. For my morning double espresso, I use about 16 grams of ground coffee to 30 ml of water. To prevent coffee getting too bitter, generally it’s better to reduce extraction time and increase the amount of ground coffee than the other way around.

2.2.2. Extraction temperature

Extract your coffee too hot, and the desirable aromas will evaporate before you have a chance to enjoy them. Too cold, and they won’t be extracted at all. The 90 Celsius point works well for brewing. Drinking temperature will be considerably lower – 65 Celsius (150F) or lower. Protein denatures at 60-65C (140-150F), so any hotter and you will be destroying your taste buds by denaturing the protein of your mouth.

As cold-brew enthusiasts have discovered, it turns out that extraction at much lower temperature for a longer time works too. Since various compounds have different physical properties, some of the aromas that are had with hot extraction won’t be present in a cold brew. On the other hand, some of the more volatile compounds that find their way into a cold brew will be lost very quickly in a hot brew. Hot brew coffee and cold brew coffee are two entirely different drinks, made out of the same two ingredients. Preparation is everything.

2.2.3. Pressure

Extracting at higher pressure will extract more aromatic compounds. If you like filter-style coffee, try an aeropress; this will give you filter-style brew, but the added pressure will make it more aromatic than a plain filter brew. If you like strong coffee, an espresso maker is the way to go. For the most aromatic, tasteful coffee, I’d recommend against any brewing method that involves boiling the coffee – Sorry mocha pot lovers, that includes your favourite preparation method. If you have an espresso machine, you may use either a pressurized portafilter basket or an unpressurized one. As you get more experienced in making espresso coffee, you’ll develop a preference for the unpressurized basket as it’s easier to clean, but it’s a little bit harder to obtain a nice crema with an unpressurized portafilter – only fresh coffee will result in a nice layer of crema sitting on top of your shot.

2.2.4. Grind

The right grind will help make your coffee taste as good as possible. Too course and your coffee will be weak and acidic; too fine and it will be bitter. Always grind to order. A burr grinder will give you better control over the grind size than a blade grinder, and will generally result in a better coffee. Coffee freshly ground with a blade grinder will still taste vastly better than pre-ground coffee a day after opening. If you grind with a blade grinder, time your grinds – I find 15 seconds works reasonably well for espresso-style coffee. If you choose a burr grinder, get one that is able to grind anywhere from “too course” to “too fine”.

2.5. Extraction time

If you don’t extract long enough, your coffee will taste weak and flat. Too long and you’ll start extracting quinic acid, which makes coffee taste bitter. Which means, don’t leave that coffee sitting in that French press once it’s done! In case of espresso brewing, extraction time correlates with extraction volume – I recommend pulling your shot right into a small measuring cup. When I reduced the size of my coffee cups, the taste of my coffee greatly improved because it was harder to over-extract it.

2.6. Crafting the coffee cup

Each preparation method and coffee-making contraption requires different skills to get the best out of your coffee. This is highlighted the most in making espresso based coffee drinks – nobody goes on a week-long course to learn to use a capsule coffee maker to its maximum potential. When we observe a trained barista make a coffee, every move they make has the same purpose: To make the best possible cup of coffee.

Between brew cycles, the coffee maker is wiped and rinsed to ensure no old grounds are left behind as these might add stale and/or overextracted notes to your coffee. Likewise, any old, stale grounds are purged from the grinder, especially at the beginning of the day. For the first coffee of the day, some dry rice or grinder cleaner may be run through the grinder to clean the burrs, after which this is purged with fresh beans. Strictly fresh roasted coffee beans are then ground, on the spot, and to order for the freshest brew.

While the grounds make it into the portafilter, the portafilter is rotated for the most even possible distribution of coffee grounds in the filter. The filter may be shuffled around a bit and tapped to the bench to help the grounds settle. Any grounds heaped on top are spread out evenly, often in a “NSEW” (North South East West) pattern. Excess grounds are removed, leaving a perfectly level un-tamped body of coffee. The grounds are then tamped with a tamper – it is twisted while the finger of the barista moves around the rim of the portafilter to ensure a perfectly level, compressed coffee puck in the portafilter basket. All these movements have as purpose to make the coffee grounds be distributed in the portafilter as evenly as possible. This forces any water to flow evenly through all the coffee, rather than only finding the path of least resistance and creating a “channel” through the grounds. The problem with channeling is that it would cause some of the coffee grounds to be overextracted – resulting in bitterness – while the aromatic oils from the rest of the coffee never make it into the cup.

The coffee shot is then pulled – by far the least interesting step of the process. Care is taken not to leave the water running for too long.

The cup of coffee is given a swirl or stir – this will help the denser, more aromatic coffee at the bottom of the cup blend with the lighter, less aromatic coffee sitting at the top.

2.6.1. Tweaks

One might pre-wet the grounds with a few drops of cold water prior to extraction – I find this results in a more complex cuppa with my espresso machine. Others run their espresso machine for a second and then wait, before the timed extraction.

2.6.2. Blasphemous tweaks

Once in a while I like adding some flavouring ingredients to the portafilter – And yes, I know, right? I blaspheme, but not quite as badly as if I were to flavour my coffee with all manner of syrups.

As it turns out, ground coconut, hazelnuts, cardamom or ginger work well in small amounts and can give a nice touch to the flavour of the coffee, without making it sickeningly sweet. I found cocoa powder would clog up the portafilter, as does ground cinnamon – but one can provide a stick of cinnamon for stirring, stir in some cocoa powder after extraction, or serve a cube of chocolate by the side.

2.7. Roast

Get ready for more rabbit-hole.

So far, I’ve discussed water, beans, preparation method and suggested some brewing tweaks. Hopefully these help you along to make a better cup.

But the single biggest thing you can do to improve your coffee is to get beans that are roasted perfectly to your liking. Darker roasts tend to have more body (up to a point); lighter roasts tend to have more aroma and tend to be more acidic. Achieving the perfect roast is a matter of balancing the two, and perfection to be found on a very fine line indeed.

Roast darker, and you’ll progressively taste less coffee and more roast. Roast far too dark, and the quality of your beans no longer matters because it will lose all subtle aromas and taste burned. Choose a two-tailed mermaid as your company logo and call it a day.

To be fair, the pre-roasted coffee beans from your local supermarket may well be fine. They’re roasted by experts with consistent results in mind. They’re also roasted very much to provide you with an inoffensive, middle-of-the-road coffee, tasting just like coffee but otherwise without much character, tending to err on the side of a darker rather than a lighter roast.

You can do better than that with hardly any extra effort; There are places that sell coffee online and that will roast to order for you. Ordering freshly roast specialty coffee on-line is a low-fuss kind of way to get some pretty darn good beans in.

But you haven’t truly lived coffee unless you have roasted your own.

2.7.1. Green coffee beans

Ordering your green coffee beans on-line is the simplest way. Alternatively, search for coffee places in your town who roast and sell their own beans – they may be willing to sell you unroasted, green beans. On eBay, looking for “green coffee beans” will result in all sorts of nonsensical superfood results – search for “home roasting coffee beans” instead.

2.7.2. Roasting equipment

There are many ways to roast coffee – from simple pan-roasting to dedicated coffee roasting gadgets. Whichever method you use, having some way to control the temperature of your roast will greatly improve the quality of your roast. I found my trusty infra-red thermometer to be an invaluable tool.

If you’re like me, before investing hundreds of pounds/euros/dollars into dedicated roasting equipment, you’ll want to know if home-roasting is for you. So we’re left with cheap options. Here are some methods I tried.

2.7.2.1. Wok-roasting or cast iron pan roasting

Simple and hands-on. Therapeutic. Also, pretty slow going. Be prepared to spend 15-20 minutes continuously stirring your beans. The results aren’t great – the contact heat leaves some dark spots on the beans. Plain and simple – this is not the way to go.

2.7.2.2. Oven roasting

In theory, this sounds good – the maximum temperature of your typical domestic oven makes it, in principle, hot enough to roast coffee beans. But the typical domestic oven also has some trouble getting to its maximum temperature, and at the end of the roast we need just that little bit more power. Still quite slow. Not the result I was looking for.

2.7.2.3. “Dog bowl and paint stripper” method

We’re on to something there. Roasting takes vastly less time this way, and we can exercise a good amount of control over the roast. No more contact heat burns, and the coffee beans puff up nicely this way. But my cheap heat gun didn’t like to be switched on for too long at a time and started making strange noises after a while. It might work for you.

2.7.2.4. Popcorn popper method

We’re entering “Hey, this actually works pretty well” territory. 1200 watts worth of heat does a pretty decent job at roasting coffee. I voided the warranty of my first popcorn popper on the day it arrived and broke it. It turned out there were two heating coils in it, one always on and one only when the fan is blowing. The first coil blew out soon after I stopped the fan. Whoopsie.

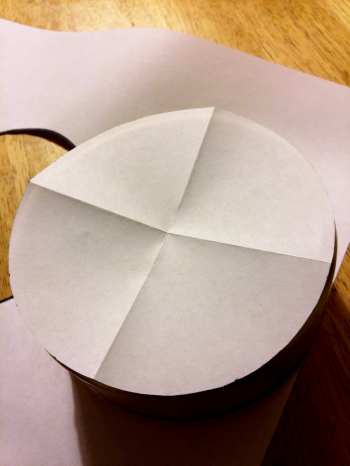

I got another hot air popcorn popper of the same model and this time left it unmodified. During roasting, I leave the plastic hood off, as this hood is known not to deal particularly well with prolonged heating – but I found that this allowed the coffee beans to pop just over the edge of the popper. I needed some sort of chimney.

I found my ideal chimney in a French Press style coffee glass. Not only was the glass exactly the right diameter – the metal base would provide me with a way to hold that glass in place.

Removing the handle and cutting off the ring stop from the bottom of the base took a while, but was easy enough with a rotary tool. Once I could mount the glass into the base upside-down, I simply dented the middle ring to prevent the glass from falling down further – although I probably needed have worried, since it was a pretty snug fit. Cutting the bottom off the glass was harder. Designed to withstand a good amount of temperature shock, the usual “score and shock” method for cutting glass proved fruitless. I ended up using a diamond cutting disc in my rotary tool instead, and was lucky enough to manage (it would have cost me a whole pound and a half to get another one).

Removing the handle and cutting off the ring stop from the bottom of the base took a while, but was easy enough with a rotary tool. Once I could mount the glass into the base upside-down, I simply dented the middle ring to prevent the glass from falling down further – although I probably needed have worried, since it was a pretty snug fit. Cutting the bottom off the glass was harder. Designed to withstand a good amount of temperature shock, the usual “score and shock” method for cutting glass proved fruitless. I ended up using a diamond cutting disc in my rotary tool instead, and was lucky enough to manage (it would have cost me a whole pound and a half to get another one).

The resulting chimney looks the part and has served me well ever since.

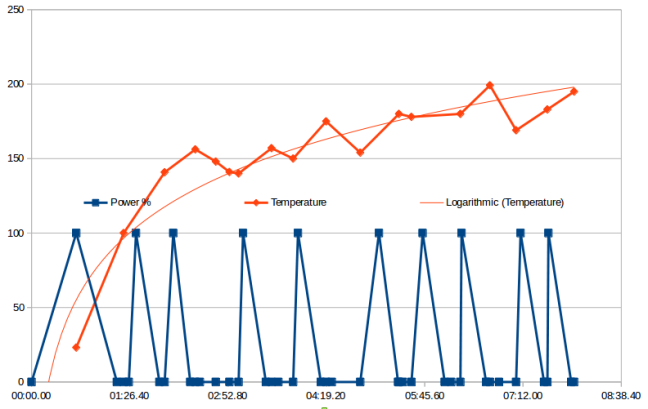

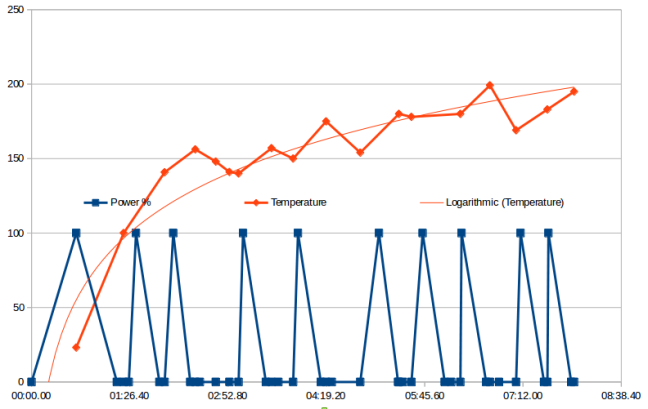

Initially the beans may be too dense to be moved by the air flow. As we want an as even possible roast, I tend to use a chopstick to agitate them and help distribute the heat. Once the beans start popping, they’ll be light enough to be stirred by the air flow, and we get a bit of a fluid bed coffee roaster thing going on. Not too shabby. Using this method, it is possible to go from green to roast in about 7 minutes, give or take (which is quite fast – professional roasts supposedly take about twice that). Soon enough I learned that playing with the on/off button during the roast allowed some degree of temperature control, resulting in better roasts. I learned a thing or two about coffee chemistry online – I suggest you follow the link for yet more detail, as that’ll save me repeating the same information. What I didn’t learn was what matter to me most – exactly how to roast my coffee to best match my own personal taste in coffee. By previous experimentation I did however find out that there’s a sweet spot around 150°C – if the roast is kept around that temperature for a while longer, the result is a smoother cup. There’s a phase at which the coffee starts to smoke a lot – at this point it gains body and loses both acidity and identity. I like to balance the roast such that there’s not too much acidity left, but the identity of the coffee is not lost. Unfortunately, it is hard to consistently achieve this balance, even when taking notes. I soon started doing 2 batches at a time; when one batch turned out slightly too light, I could roast the next batch slightly darker and mix the two together. This provides a means to blow away most coffee houses in town.

Initially the beans may be too dense to be moved by the air flow. As we want an as even possible roast, I tend to use a chopstick to agitate them and help distribute the heat. Once the beans start popping, they’ll be light enough to be stirred by the air flow, and we get a bit of a fluid bed coffee roaster thing going on. Not too shabby. Using this method, it is possible to go from green to roast in about 7 minutes, give or take (which is quite fast – professional roasts supposedly take about twice that). Soon enough I learned that playing with the on/off button during the roast allowed some degree of temperature control, resulting in better roasts. I learned a thing or two about coffee chemistry online – I suggest you follow the link for yet more detail, as that’ll save me repeating the same information. What I didn’t learn was what matter to me most – exactly how to roast my coffee to best match my own personal taste in coffee. By previous experimentation I did however find out that there’s a sweet spot around 150°C – if the roast is kept around that temperature for a while longer, the result is a smoother cup. There’s a phase at which the coffee starts to smoke a lot – at this point it gains body and loses both acidity and identity. I like to balance the roast such that there’s not too much acidity left, but the identity of the coffee is not lost. Unfortunately, it is hard to consistently achieve this balance, even when taking notes. I soon started doing 2 batches at a time; when one batch turned out slightly too light, I could roast the next batch slightly darker and mix the two together. This provides a means to blow away most coffee houses in town.

But there are a few professional roasters in town that refuse to be bested by an amateur home roaster who merely roasts by trial and error. I needed structural, progressive improvement.

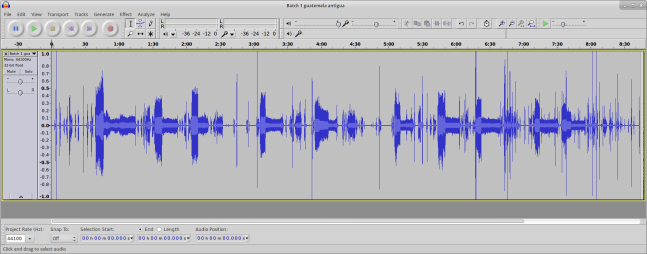

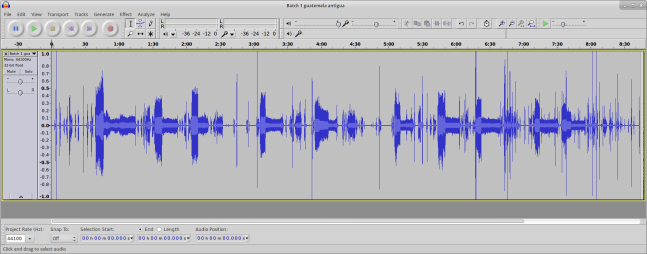

It wasn’t practical to merely keep notes on what I did when a roast turned out particularly well. There were simply too many on/off cycles to get a roast to be exactly the same every time. I needed more control. I started thinking about how I’d make my roasts more measurable and reproducible. I realized that an easy way to record the roast was by recording an audio file of the roasting process.

This clearly showed me at exactly which point I switched on and off the popcorn popper. While roasting the coffee, I’d also take temperature measurements with my infrared thermometer and speak them out. The resulting audio file ultimately allowed me to feed the data points into a spreadsheet and plot temperature over time, with a minimum of hassle to collect the actual data.

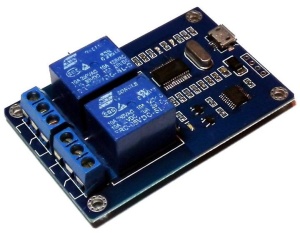

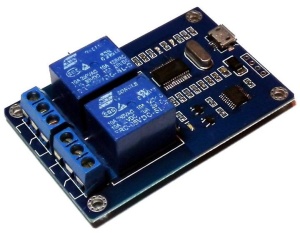

More importantly, it provided me with a way to reproduce the roast. I could do this by simply playing back the audio file and mimicking what I heard. Instead, I decided I wanted to automate my roasts. I could store the on/off times in a file and turn the popcorn popper on and of by computer. This turned out to be surprisingly simple with a USB-driven relay. As a 1200 Watt popcorn popper at 240 volt clocks in at 5 ampere, I figured a circuit board with 2 10-amp relays would do nicely.

I chose a board with 2 relays in case at any point in the future I wanted to add a cooling fan. I proceeded to build it into a project box – only basic electrics skills required. At this point, what I had was a box that permitted me to switch on and off mains power to basically any electric device – in this case a popcorn popper. A rather elegant solution; note that essentially this popper is still unmodified. Add a small script (I’ll gladly provide you with it) and the computer can control switching on and off the popcorn popper – or any other device for that matter.

I chose a board with 2 relays in case at any point in the future I wanted to add a cooling fan. I proceeded to build it into a project box – only basic electrics skills required. At this point, what I had was a box that permitted me to switch on and off mains power to basically any electric device – in this case a popcorn popper. A rather elegant solution; note that essentially this popper is still unmodified. Add a small script (I’ll gladly provide you with it) and the computer can control switching on and off the popcorn popper – or any other device for that matter.

|

Update: The micro USB connector came off this circuit board, so I ordered in a circuit board with a sturdier connector. As I’m writing this, it hasn’t arrived yet. In the meantime I’ve updated my roasting script so it can support multiple device types.

As I had nearly run out of roasted coffee, I saw the merits to also allowing the script run without automated switch box. When doing so, the script simply prints “ON” and “OFF” to screen, allowing one to perform a computer-aided roast by switching the popcorn popper on and off as indicated by the script.

Update 2: The new USB controller board has arrived. I have added drivers to the roasting software to auto-detect which board is present. |

|

this still doesn’t provide us with real temperature control, in practice this isn’t much of a hurdle. One; when starting with similar starting conditions and performing exactly the same operations at exactly the same time, the result should be pretty similar. By tasting a roast, I can now make progressive adjustments to the roasting procedure until it tastes just right – so far this has resulted in the best cup of Guatemala coffee I’ve ever brewed. I can take two different roasting profiles and compare them side-by-side to determine which of the two is the best.

And if this solution no longer serves me, I can always add proper temperature control.

Currently I use my PC to control power, but there’s no reason why it would have to stay that way. The used controller board provides serial pins and could be controlled by Arduino, or a credit-card sized single-board computer such as the Raspberry Pi could be used to control the power (In the latter case I wouldn’t even need to write a new script). It could still easily be added inside the project box, creating a dedicated coffee roasting box.

Once your roast has completed, you may notice a few beans that are considerably lighter in colour than the others. These are called floaters and they’re beans that have a very low amount of aromatic compounds in them. If you munch down on these beans, you’ll find they taste a bit like popcorn and not at all like coffee. Discard these beans, they add nothing to your cup.

2.7.3. Tasting

Finally, the most important thing about your cup of coffee – tasting it, or as it is called in official terms, cupping. There are standards on how a coffee should be prepared for tasting, but for personal use I suggest to prepare the coffee as you would normally drink it; It seems pointless to me to brew a filter-style cup of coffee if all I ever drink is espresso, as it doesn’t give me a meaningful frame of reference. I would however suggest to brew your coffee in a way that you can reproduce perfectly identical, time after time. It makes sense to let the coffee beans develop their taste for a few days. It allows the oils in the coffee bean some time to absorb the flavour. Also, at the very early stages after a roast, the coffee beans still emit carbon dioxide which would dissolve in water and form carbonic acid, which alters the flavour of the coffee.

If you ever wondered why coffee hardly ever comes in vacuum packed bricks anymore, carbon dioxide is the reason; coffee can only be properly vacuum packed once it no longer emits gas, which means letting it breathe for a few days. This takes both storage space and time, and ultimately doesn’t benefit the coffee. Also, of course, the valve in modern coffee packs permit you to smell your pre-roast coffee before buying it. It’s simply good marketing.

Incidentally, it is also carbon dioxide which is responsible for the crema on top of your shot of espresso, and hence a good crema is an indicator of the freshness of your coffee – unless, of course, the crema isn’t really crema but foam whipped up in a foaming chamber.

Hello, companies who add foaming chambers to coffee makers: Foaming chambers don’t magically make the coffee fresher. Stop lying to us.

2.7.4. Enjoy your coffee!

I like coffee. Especially if it’s good coffee. And now that I have the tools to make a cup that’s perfectly tailored to my personal taste, I’ve got that covered.

Once you’ve gone through these steps, it’s likely you can now enjoy a pretty decent cup of coffee – and isn’t enjoying your coffee the most important step of all?

May you drink many good cups of coffee. I hope you’ll enjoy your coffee as much as I enjoy mine.

Left: Ginger / Jahe, right: Galangal / Laos/ Lengkuas

Left: Ginger / Jahe, right: Galangal / Laos/ Lengkuas Asam kandis (Garcinia xanthochymus) is not available where I live,

Asam kandis (Garcinia xanthochymus) is not available where I live, Left: Salam leaves, right: Bay leaves.

Left: Salam leaves, right: Bay leaves.